“My rule of life prescribed as an absolutely sacred rite smoking cigars and also the drinking of alcohol before, after and if need be during all meals and in the intervals between them” – Sir Winston Churchill

I’VE long been interested in the way people view wine. Some see it as an aspirational drink, others as a snob’s drink, but down the years it’s been a civilising factor and can be a valuable growth industry post-confilct.

The Nazis couldn’t wait to get their hands on the wine treasures of France, which is quite surprising considering the top officials were more often than not lunatics, and Churchill allegedly guided the Allies to war on the stuff. Indeed, wine was the chosen drink of the Roman Empire for officers and men alike and they did rather well for civilisation as a whole, even if their methods were less than genteel.

In more recent times, wine-making has expanded into the once fractious lands of the Lebanon with the efforts of that country’s father of wine, Serge Hochar, remembered with many international awards.

And as I found out last summer, it’s an industry that Sir Bob Geldof is keen to expand in Ethiopia because of the export potentials which are always more likely to be of interest than locally-grown tatties.

What is it about wine, then? Is it the fact that – like many other forms of agriculture – you have to add patience into the mix whereas beer and lager can be produced and bottled in days? Or is it, like many French winemakers would like us to believe, something far more magical that sets wine against almost all other alcoholic drinks?

Whatever it is, I was intrigued this week by a news report of a very determined wine-maker in Syria, of all places. Ravaged by civil war and terrorist attacks, it seems the least likely place in the world to grow vines but then I thought that in 1987 when I first heard about Serge.

The vineyard is based on the same location as a long-disused Roman one and is run by brothers Karim and Sandro Saade who can no longer directly manage the vines as the danger to themselves is so high.

They have recently been forced to move production to the Lebanon where they have another vineyard but the efforts these two brothers go through to get the cork in the bottle is spellbinding.

They have to get the grapes transferred to their office in Beirut – a 125-mile journey over some of the most contested land on earth right now, and that’s just so they can sample them and decide when its right to pick.When the grapes are ripe, the 35 local families who depend on this land for their income pick them by hand and truck them over the same dangerous route to the brother’s winery in the Lebanon, Chateau de Marsyas.

They focus on the big-ticket varieties much loved all over the world of Chardonnay and Sauvignon for the whites and Cabernet, Merlot and Syrah for the reds. At this point it’s worth mentioning that the vineyard is bombed a few times every year, they think by extremists as the area is still under Assad’s control. Another reason to suspect ISIS is that they are producing an alcoholic drink which is forbidden under strict Islamic law.

It’s quite remarkable, therefore, that the brothers manage to produce 45,000 bottles a year which are exported through a long and tortuous route from the Lebanon to Egypt, then to Europe and the rest of the world via Port Said and Antwerp.

Karim describes the whole experience from vine to bottle as an act of resistance and a symbol of perseverance in a dangerous world. I can’t personally recommend the wines from Ch de Maryas because I haven’t tried them yet, but watch this space because if anything is worth risking bombs to create, I think it’s only decent that we bring some to Whitehaven to try it.

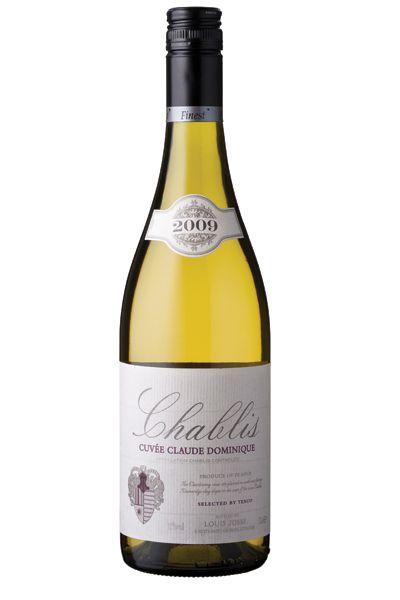

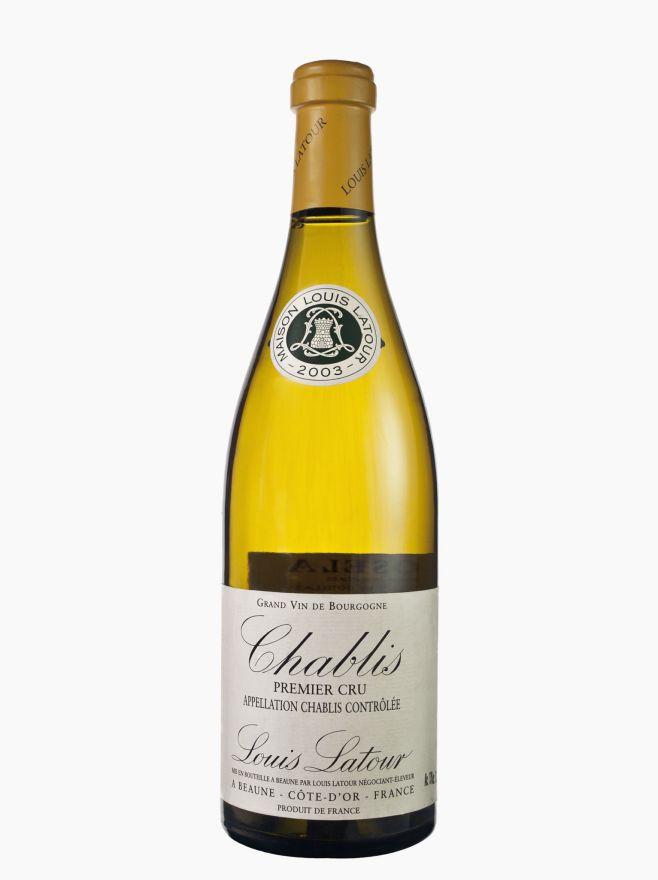

In the meantime, what I am going to recommend today is another great wine for the summer but whatever you do, don’t go cheap on this one: It’s Chablis.

Chablis is one of the great white wines of the world, but as with all greats there are one or two charlatans out there so do go for a major producer or well-known name. In fact 50 years ago there were only 400 hectares of vines in Chablis; there are 4,900 today.

Chablis is grown in the northern region of Burgundy where the predominant sub strata is limestone, which helps give the wines their intense mineral flavours which have made Chablis one of the very few wine styles in the world that can be copied.

Personally I think there are very few pleasures in life as good as a decent Chablis and I’ve made a point in business of only stocking the best, which I believe to come from Louis Latour and J. Moreau. Latour produces a crisp, deep wine with intense complex flavours of fresh acacia fruits and minerals with the classic steely finish you expect.The finish tends to be slightly honeyed and exceptionally clean.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here