Few missions in science are more fascinating than the quest to find alien life.

So a claim by researchers that the clouds enveloping Venus may contain microbial life – potentially indicated by the presence of a gas called phosphine – understandably caused intense international interest.

It took a scientist led by a former north Cumbrian man to show that this claim couldn’t – quite literally – hold water.

Dr John Hallsworth has fond memories of spending his early adolescence in Gaitsgill, near Dalston.

A former pupil of Caldew School, with a lifelong fascination for plant science, he has become a leading authority on the physical limits of life – a subject at the heart of so-called ‘astrobiology’.

Over 14 gruelling days, John, a 53-year-old father of two, led a team of academics as they set about proving why microbial life could not thrive in the clouds of Venus.

Those clouds are composed mainly of sulphuric acid – deadly for the cellular structures that support life.

“We looked at the [clouds’] concentration of water molecules, scientifically called water activity,” John explains.

“Not only did we find the effective concentration of water molecules are slightly below what is needed for the most resilient micro-organism on Earth; we found that it’s more than 100 times too low.

“It is almost at the bottom of the scale and an unbridgeable distance from what life requires to be active.”

Now based at Queens University in Belfast, John’s path to academic success has been littered with discoveries.

As a child, he spent hours ‘communing with nature,’ studying the plants and insects he found near the housing estate north of Manchester where he spent his early years.

“There was an area of rough ground with muddy puddles, ravines, wild orchids, bees; and a stream with sticklebacks,” he says.

“In 1984, when I was 16, we moved to Gaitsgill and I spent a lot of time walking and cycling around, absorbing the wildlife and natural world.”

He did his A-levels at Caldew School, studying biology, chemistry and maths.

In his spare time, John became fascinated by exotic plants, including sub-tropical trees.

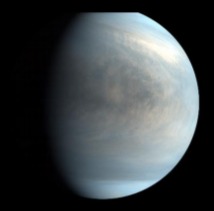

VENUS: Pictured by the Japanese Space Agency

He imagined a future in horticulture. Yet his academic life – initially a plant biotechnology degree at Wye College and research with a biotech firm – gave him an enduring fascination for microbiology.

He experimented with fungicides and yeast cells, investigating the factors which inhibit or or destroy their capacity to live.

“As much as I’m enchanted by the beauty of natural world, once you get into the cell at that kind of level, there’s the same kind of beauty,” he says. “I fell in love with the idea of studying micro-organisms.

“I’d realised the beauty within microbial cell.” He completed a PhD at Cranfield University, held various post-doctoral posts and eventually became a lecturer in the School of Biological Sciences at Queen’s University in Belfast.

Earlier in his career, John had penned an influential paper that explained how ethanol – pure alcohol – unravels and disorders the structure of cells.

Later came a perhaps an even more important discovery: how some microbial cells can function in even more arid conditions than was previously thought possible.

For 20 years, John collected scores of fungi samples from across the globe, hoping to find one capable of active life at hitherto unheard of levels of aridity.

“Bizarrely,” says John, “the fungus which came through was one from inside my house.

It was from a dusty crevice on the an ornamental owl – a fungus called "apsergillias penicilliodes.”

It’s a common fungus, often seen as brown spots on old books or less obviously on pillows and duvets, where it is routinely devoured by the dust-mites.

John’s revelation – that cells could function at considerably lower levels of humidity than previously thought possible – extended the known limit of life on earth.

Microbes which can survive in harsh environments – such as hot deserts, hot hydrothermal vents or even in highly radioactive areas – are known as extremophiles.

They are central to the science of astrobiology because it is likely that alien life if it is ever discovered is likely to be microbial and may well exist in just such an environment.

John’s expertise in this field is what has made him an asset to Nasa (National Aeronautics and Space Administration) in the United States.

Experts there have signed up to an international policy on planetary protection.

It aims to prevent space explorers accidentally contaminating pristine alien worlds.

“The other part of this is to make sure we don’t accidentally bring some dodgy life-form back to earth,” says John.

“The policy says that you can’t land a spacecraft in a location – for example on Mars – where conditions might allow microbes to proliferate.

“On Mars, those places are called Special Regions because, theoretically speaking, there could be some kind of extremophile from earth which could contaminate a spacecraft and get there.

“If it did, it could plausibly proliferate.

“That policy is based on two things: the most extreme temperature for life on earth and the most extreme water activity [humidity] for life on earth.”

In 2012, Nasa’s head of planetary protection contacted John and invited him to join an expert panel for life detection.

It was convened to decide what kind of samples should be collected in the ongoing Perseverance Rover expedition to Mars.

“I’m not an expert in life detection,” says John. “But I did contribute; and a year later, I was invited on to another panel to determine the Special Regions on Mars where life could proliferate.

“It was made up of 22 scientists - 18 from America, two from Canada, one from Germany, and me. It ran for eight months: we have weekly teleconferences calls, thousands of emails, and three meetings in the States.”

The panel’s research created what has become the foundation for international policy on planetary exploration.

Since his move into astrobiology, John has been invited to several Planetary Protection Panel meetings at the Lunar and Planetary Science at Institute of Nasa in Houston, Texas.

He has also visited Johnson Space Centre where astronauts are trained and from where the International Space Station is controlled.

Does he believe alien life will be discovered?

He says: “I think it’s out there somewhere, though we’re fairly restricted to looking within our solar system. If we do find it, the evidence will be indirect and long distance.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel