PETER Giesecke was watching television in his living room when unimaginable horror unfolded on the evening of December 21, 1988.

His children were upstairs in bed and his brother-in-law had called around to wrap Christmas presents for his sister.

“The TV was on. It was 7.03pm when it happened,” recalled Peter, 65, a retired Royal Mail motor technician who was latterly based at Junction Street in Carlisle.

“We heard this rumbling. It sounded like thunder, getting louder and louder.

“I went to the window, opened the curtains and all I could see was a bright glow in the sky.

“Seconds later, oh God, there was an explosion. The windows blew in. There was such a blast that it blew the freezer door open.”

Then everything went dark.

“The kids were upset,” Peter continued. “They came down screaming. They didn’t know what was happening.

“All hell had let loose.”

His brother-in-law, a part-time firefighter, left immediately.

What they would see in the minutes and hours that followed they could never have imagined - scenes that would throw their community into international spotlight in the worst possible circumstances.

Unsure what had happened, Peter made his way into the kitchen of his home in Park Place, Lockerbie.

“I got through the back door,” he explains. “There was rubble, stoor and bits of plane. I’d managed to find a torch and was shining it all about.

“I shone it on to the hedge and I could see something on it. It was a body. I can always remember, she was face down, this girl. She had one shoe on.

“I got such a fright. There was rubble all over the place. The amount of stuff that was in the garden was unreal.”

Next door, the entire side of Ella Ramsden’s house had been torn down as debris from what they later found out was Pan Am flight 103 fell from the skies above the small market town.

Remarkably, she escaped unhurt. Had pieces from the aircraft fallen fractionally differently, neighbours were sure that her entire house would have been wiped out, with tragic consequences for her.

Photographs taken by father-of-three Peter the next morning showed the scale of the damage to her house and the devastation that had rained down on his garden.

“What a mess there was. It was unbelievable,” he says. “A big part of fuselage was propped up against my bathroom window.

“We were very lucky up here that no-one had been injured.”

The Park Place and Rosebank Crescent area was a scene of devastation as debris – and, heartbreakingly, bodies – fell on Lockerbie. The remains of more than 60 people were eventually removed from that part of the town.

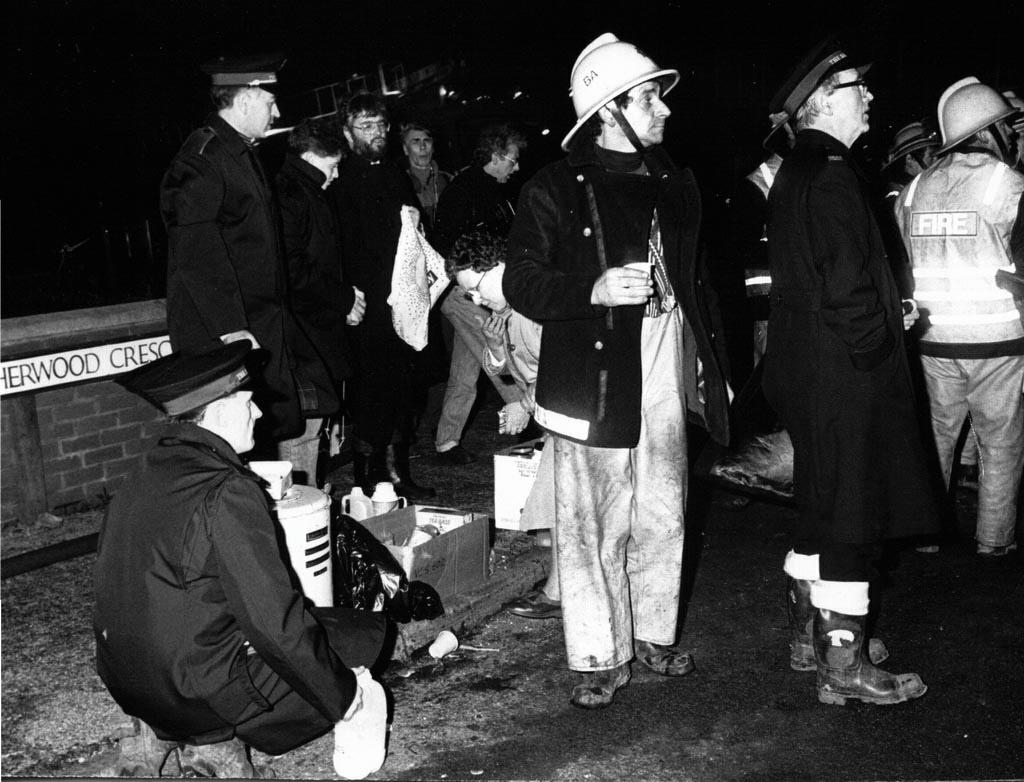

In Sherwood Crescent – close to the main A74 Carlisle-Glasgow road – that falling aircraft caused a huge explosion that wiped out houses and created a giant crater.

Eleven Lockerbie residents were killed there.

All 259 passengers and crew on-board Pan Am flight 103 died also.

Victims ranged in age from two months to 82 years. In all, they were from 21 nations.

Lockerbie was never the place over which the plane – bound for New York’s John F Kennedy Airport – was supposed to blow up.

It was intended for the attack to take place over the Atlantic Ocean, but a delayed departure from London Heathrow meant that the Dumfriesshire town was the place where tragedy struck, a bomb concealed inside a radio cassette recorder exploding at 31,000ft.

Images of the horrors in Sherwood Crescent – where homes were ablaze on the night – and Rosebank Crescent were beamed all over the world.

So too was what was to become the defining image of the disaster – the crumpled nosecone of the Boeing 747 jumbo jet, Clipper Maiden of the Seas, lying on a hillside close to Tundergarth Church, three miles outside of Lockerbie.

The dignity with which townsfolk and emergency services treated those who died – and whose legacies will be remembered with pride today - has never been forgotten.

Most of those on-board the flight were Americans, 35 of them students from Syracuse University in New York State.

Lindsey Otenasek, a 21-year-old from Baltimore who aspired to be a teacher, was among them.

Her mum, Peggy, was one of the many relatives of victims who visited Lockerbie in the wake of the disaster, with townsfolk recognised worldwide for the compassion they showed – and continue to show – to those who visit to pay their respects where their loved ones died.

It was Lindsey who Peter had found.

Recalling how he and Peggy met in the months after the bombing, he said: “I was in the garden when this lady came with another lady. She asked if it was ok to come into the garden.

“She said ‘I’m Peggy Otenasek. My daughter was found in your garden’. She told me she could pinpoint exactly where she had been found.

“I was able to show her exactly where her daughter had lay. She couldn’t believe that I had seen her there. We chatted away and went for tea.

“When she was here, I picked up a pebble in the garden. It was really smooth. I washed and cleaned it then said to her ‘take that back home. That will remind you of where your daughter was found’.

“I gave her a hug. She’s such a nice woman. To meet her was unbelievable.”

The pair have kept in-touch since, Peter and his wife Susan, 53, having an open invitation to visit Peggy in Baltimore.

Such was the affection that she feels for Lockerbie townsfolk, that when a group of fundraising cyclists from Lockerbie embarked on a memorial cycle ride to Syracuse this summer, she was determined to meet them.

She had in her hand the pebble from Peter’s garden.

Retired police sergeant Colin Dorrance, one of the cyclists, said: “Half of her family were there to support us. At 85 years old she said she felt this was her last chance to have a connection with Lockerbie.”

Peggy’s gratitude for townsfolk symbolises the bonds which have been forged out of the tragedy of three decades ago.

Many people in Lockerbie have long felt detached from the legal and political issues that have existed since the disaster. Their connection to what happened is on more personal level.

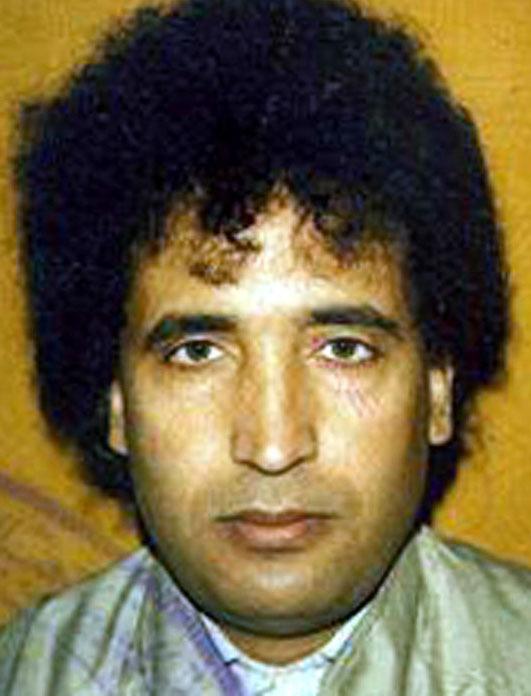

Former Libyan intelligence agent Abdelbaset Ali Mohmed Al-Megrahi was convicted following a trial at a special court in the Netherlands and sentenced to life in a Scottish prison in 2001.

He was released on compassionate grounds – in the face of international condemnation - in 2009 after being diagnosed with terminal cancer. He died in Libya in 2012, continuing to protest his innocence.

There are many – including some relatives of those who died – who believe he was not the man responsible and are continuing a legal fight to clear his name.

Peter Giesecke, however, is doubtful that the truth will ever be known.

“A lot of people in Lockerbie do want to forget about what happened, but I think we have to remember,” he said. “There were a lot of lives lost.

“It’s maybe just me, but I think Megrahi was just a scapegoat. More people were involved than that. They will never find the true story.

“That plane was meant to have blown up over the Atlantic. If that had happened, there would have been nothing to find.”

Victims of the disaster will be remembered today in a ceremony organised by Lockerbie Community Council and involving broadcaster Fiona Armstrong, the Lord Lieutenant of Dumfriesshire, in Dryfesdale Ceremony, home of a memorial to all those who died.

At the wishes of townsfolk, it will be a low-key affair. Wreaths will also be laid at smaller memorials in Rosebank and Sherwood Crescents.

Dumfriesshire MP David Mundell, the Scottish Secretary who grew up near Lockerbie, will be among those paying his respects.

He said: “Today is about families and friends of the 270 people who died completely randomly and everybody else whose lives have been affected by these events. It’s about remembering them.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel