MORE schools are struggling to balance their books under increasing levels of debt in Cumbria than any other part of the country.

A total of 48 primaries and secondaries slid into the red last year - the highest figure of any local authority nationwide - according to the information released by the Department for Education.

The increasing number of cash-starved schools has now been described as a 'powder keg that will at some point go off' by union officials who claim the government must ensure education in the county is funded properly.

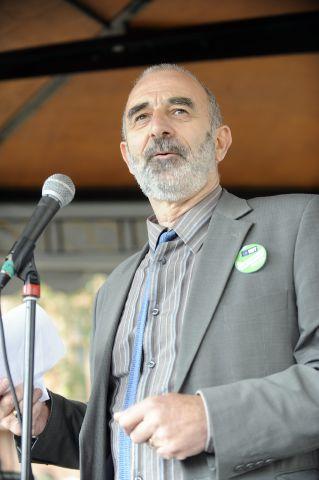

Alan Rutter, assistant secretary of the NUT in Cumbria, called upon the government to consider the county's education budget as a 'special case' .

"Cumbria is funded using the same formula as Kensington and Chelsea.

"Now clearly, they do not have the same issues with sparsity in Kensington and Chelsea that we do here.

"Headteachers are doing as much as they can with an inadequate budget but they have now carved all of the fat away and there's nothing left."

Mr Rutter explained the situation was expected to get worse, as more and more schools struggled the make ends meet.

"It's like a powder keg bubbling away. At some point it will go off," he added.

"Teaching staff are going above and beyond to keep going but they haven't had a pay rise near to the level of inflation in years."

Of the 48 deficit-hit schools in Cumbria during the 2016/17 year, 36 were primaries which had a combined operating debt of £1.4 million.

Nine of the county's 15 secondary schools finished the year in the red by £2.6 million.

By comparison, neighbouring Lancashire had 40 schools in deficit, Liverpool had 24 while Manchester had one.

Funding per pupil in Cumbria was £4,658, just short of the average £4,825 for the North West region.

Graham Frost, Cumbria Branch Secretary of the National Association of Head Teachers, said the increasing number of schools recording a deficit showed fears over funding levels in Cumbria were biting in real terms.

"I am hearing from members that they are reaching a point at which they will have to start cutting things they really can't do without," Mr Frost said.

"What's different about Cumbria to other areas is our geography. We have a lot of small schools which are essential to our economic and social needs.

"The cost of delivering services is affected by the landscape, and that needs to be recognised in the way education in the county is funded."

If a school is unable to balance its books it must notify the local authority, which may offer a short-term loan.

But instead, head teachers will often have to cut back on staff and equipment in order to get back into the black.

The most recent data shows nine per cent of all local authority maintained schools ran at a deficit across the country, a figure which has almost doubled from five per cent in 2014-2015.

However, that figure is 18 per cent in Cumbria.

Schools are funded mainly through a grant from the Department for Education, which allocates funds to each local authority based on demographic factors such as pupil numbers, deprivation and additional language needs.

The local authority then decides how to divide the money between individual schools.

But schools in England are facing a real-terms cut of 6.5% between the current financial year and 2020, once inflation and rising pupil numbers are taken into account, according to the Institute for Fiscal Studies.

Councillor Sue Sanderson is a former teacher and Cumbria County Council's schools and learning boss.

She said: "This references the fact that funding for schools is insufficient - particularly in a rural area like Cumbria where we have a large number of schools which have higher costs."

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here