A NEW book about the outstanding bravery of 21 men who served in the RAF and the Fleet Air Arm during World War Two incredibly features two from our area, one a former editor of The Whitehaven News, the other, a local doctor.

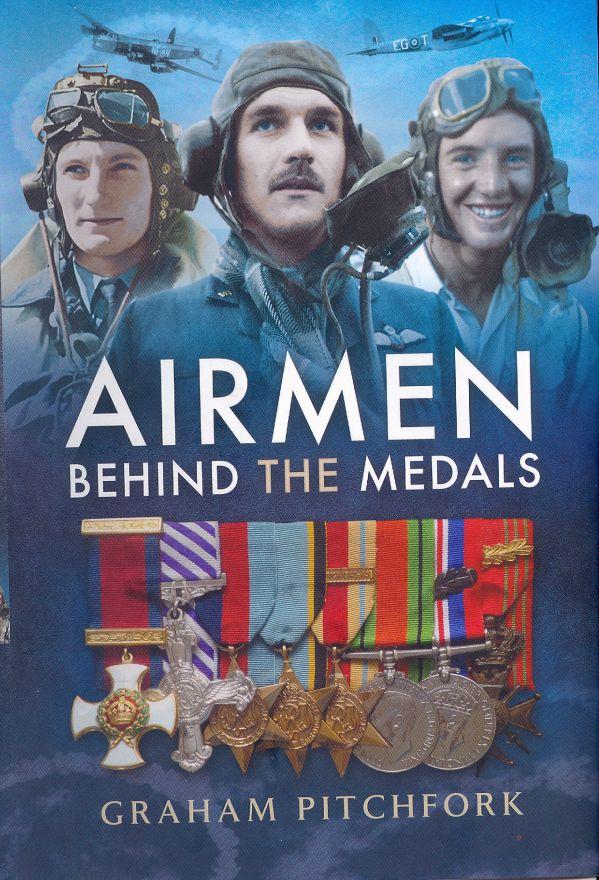

Entitled Airmen Behind the Medals by Graham Pitchfork, the accounts in this book cover many areas, different types of aircraft and stories of great courage and spirit.

Walter Thomson was editor of this paper for 20 years, retiring in 1987, having started as a young reporter under George Carter in 1948. He was highly regarded and dedicated to his readers, many of whom knew little of the young Walter’s wartime exploits as a pilot in the Fleet Air Arm which resulted in him being awarded the Distinguished Service Cross.

As soon as he had finished school in June 1940 he was to join the Royal Navy, aged 18, and went on to train as a pilot seeing early action in Mada-gascar, the Mediterranean, Norway, the East Indies and the Pacific. He won the DSC in action against Japanese kamikaze planes attacking the British Pacific Fleet.

By 1942 Thomson found himself in Mombasa flying Sea Hurricane and Fulmar aircraft before being sent to Madagascar to help secure the island for the Allies. His aircraft was hit on his final operation there and he struggled back to land after a four-hour sortie. After deck-landing training in Scotland, he joined the Seafire Flight of 833 Squadron which embarked on the carrier Stalker bound for Gibraltar, then on to Italy for the Salerno landings.

In July 1944 he left with aircraft carriers heading for northern Norway and Operation Mascot – the attack on the German battleship Tirpitz . German smoke generators and fog conditions made the task impossible and it was August before a second attempt was made. The Tirpitz remained a major threat to the Arctic convoys and Thomson was among those who took off as part of the escort for the Barracuda bombing force with it in its sights, but low cloud forced a return. Thomson made a photographic run across Tirpitz at 4,500 feet, attracting most of the flak as his observer tried to get pictures but when his Firefly was hit on the port wing by a 40mm shell he had to carry out an emergency landing on the too-small deck of the Trumpeter carrier. With his airspeed indicator no longer operating, Thomson’s skill was put fully to the test.

With the return of the carriers to Scapa Flow, the Fleet Air Arm’s attacks against the Tirpitz were over and it was left to the Lancasters to finally end the battleship’s career on November 12. Thomson was Mentioned in Despatches for his work off Norway and next he was off to Ceylon, then on to join the newly-formed British Pacific Fleet which included four fleet carriers mustering 250 aircraft.

It was in action against the Japanese kamikaze planes that Thomson’s deeds brought him the DSC. There were successful attacks on a large refinery complex at Sumatra and 34 enemy aircraft were destroyed on the ground and fighters shot down a further 14. However a heavy price was paid for the daring strike: 40 aircraft were lost, 20 due to enemy action. Among those lost was 1770 Squadron’s senior pilot so Thomson was promoted to take up his duties.

As the Americans began their assaults to recapture Okinawa, Thomson was among those given the task of preventing the Japanese using the airfields on islands south east of Okinawa. After a three-hour sortie he returned to the carrier with a malfunction that left his plane careering into the island at 70 knots, losing half the starboard wing. He was disappointed he had not managed to reached his century without a deck mishap.

While in a Firefly on a combat air patrol mission to protect a rescue boat, five kamikazes were spotted and Thomson set one on fire and chased a second which exploded.

Despite all his dangerous exploits, his only injury was when he suffered a shrapnel wound to the back while busy shaving! An Avenger accidentally fired off its guns and some of the cabins were hit and two aircrew killed. Thomson was transferred by Beeches Buoy to a destroyer before being taken to a hospital ship then returned home. Soon the war was over and he came back to Whitehaven, demobbed in 1946. After a two-year business course he joined The Whitehaven News as a reporter. Walter Thomson died in 1991, aged 69.

Heroic service as wartime medic

FOR an RAF airman to be awarded the Military Cross is a rare thing. Dr Courtney Willey, who post-war was to become a consultant physician at West Cumberland Hospital and live at Woodend, near Egremont, was such a man. During the war he frequently risked his own life to save others, in field hospitals and at a Japanese PoW camp.

In 1940 he was a commissioned flying officer in the RAF, stationed at Tangmere airfield in Sussex. He was a ground medical officer with Squadron 601 when warning was received that enemy aircraft was approaching. It was a devastating attack which resulted in 13 deaths, 20 injured and a great deal of damage was inflicted.

He organised the evacuation of patients from the sick-bay to an air-raid shelter. All were moved safely with the exception of one man who was violent. The sick-bay was bombed, the man’s clothing was blown off and he suffered burns, but survived. Dr Willey escaped unscathed when the corridor where he was also got bombed.

Pilot Billy Fisk, the first American to join the RAF, landed in his burning plane and was attended to by Dr Willey and two orderlies. All were awarded the Military Cross but sadly Fisk did not survive.

Dr Willey was posted to Singapore in 1941 and he shared a cabin with Dr John Simpson during a six-week voyage. They landed in October 1941 and in December Pearl Harbour was bombed.

In 1945 Dr Willey was awarded the MBE for evacuating personnel from Sumatra.

When Java fell to the Japanese 12,000 men were captured, of whom 5,000 at least were RAF. Willey worked in a former Dutch military hospital with the seriously sick and wounded, a place where dysentery was the main problem.

Willey arrived at the PoW camp set up at Changi Jail but was later taken by train to Siam where the Burma-Thailand railway was being constructed through 250 miles of jungle. The sick were made to work on the line and Willey found it distressing to have to select the less weak to go and work, knowing that some would not survive.

Willey was one of three RAF doctors at the base hospital at Chunkai where conditions were very bad and there were few medical supplies. There were 1,200 seriously sick patients evacuated from the jungle railway camps suffering from chronic tropical illnesses.

Then the doctors were taken 200 miles away to a place where there had been an outbreak of cholera and worked for the anti-cholera and malaria unit of the Japanese army. When the unit moved to Burma, Willey was put to work on woodcutting, rice carrying and jobs in the cookhouse. Altogether he was three years in captivity. It was January 1946 before he was released from the RAF and able to return to his medical profession.

n Airmen Behind the Medals by Graham Pitchfork is published by Pen & Sword, available from Amazon.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here